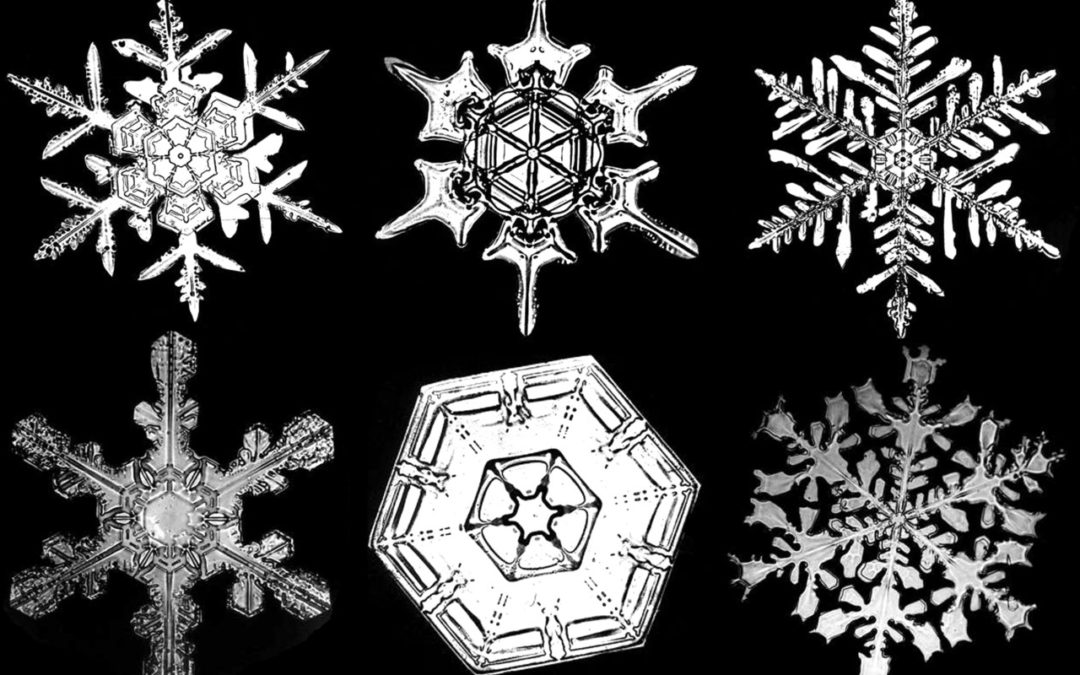

This morning upon awakening in a “mood” of snow and the cold, surrounded by a nostalgia of images–of sun dogs, and hoar frost, and the northern lights–I set out to once again exalt the singularly unique, lit-from-within beauty of dreaming. For the dreamtime never ceases to amaze me with its creative, infinite beauty–the way it’s always, always generating new images to freely give us, and how no two images are exactly the same. So, while searching through pictures of ice crystals, I stumbled upon many that were taken by William A. Bentley, better known as William “Snowflake” Bentley.

Snowflake Bentley was born in 1865 in Jericho, Vermont–an area known as the “Snowbelt,” with an annual snowfall of about 120 inches. He spent his life living and working on the family’s farm and was fascinated with the natural world that surrounded him.”But always, from the very beginning,” he said, “it was snowflakes that fascinated me most. The farm folks, up in this north country, dread the winter; but I was supremely happy, from the day of the first snowfall–which usually came in November–until the last one, which sometimes came as late as May.”

On his fifteenth birthday, William Bentley received a microscope. He spent the next two years in a small room at the back of the farmhouse peering through his microscope at ice crystals. He made hundreds of sketches of what he saw but was always disappointed with the results. One day he chanced to read that it was possible to take photographs through a microscope. Somehow, and with the help of his mother, he persuaded his father to buy him a bellows camera and a better microscope.

He experimented with the camera, the microscope, the dry plates (that were used at that time to record photographic images) and snow. He knew nothing about photography and endured failure after failure. But with patience and persistence and a genuine love of snow, on January 15, 1885, during a snowstorm, William Bentley made the first ever photomicrograph of an ice crystal.”The day that I developed the first negative made by this method, and found it good, I felt almost like falling on my knees beside that apparatus and worshipping it!” he said. “It was the greatest moment of my life.”

For the next 47 years, William Bentley went on to capture images of more than 5000 snowflakes! He was so good at it that almost no one bothered to photograph another snowflake for close to a 100 years. In an article that appeared in Popular Mechanics Magazine in 1922 entitled “Photographing Snowflakes,” he wrote: “Every snowflake has an infinite beauty which is enhanced by knowledge that the investigator will, in all probability, never find another exactly like it. Consequently, photographing these transient forms of Nature gives to the worker something of the spirit of a discoverer.”

Gives to the worker something of the spirit of a discoverer. This is exactly what it is to work with dreams! Like snowflakes, no two dreams (or dream images, for that matter) are exactly alike (even those that are referred to as “recurring” dreams). Isn’t this because no two dreamers are exactly alike? And yet every time we ask what a dream image “means” we forget this simple truth.

Like William Bentley with snowflakes, I too am “possessed with a great desire to show people something of the wonderful loveliness”–of dreams: the nature of dreaming. The good news is that with dreams no special equipment is required. All that’s needed is a dreamer and a heart that is willing to turn toward the light of dreams.

Now, no photograph of a snowflake has ever kept even a single snowflake from melting. So even though William Bentley fancied himself something of a “preserver” of snow, what he really did was to get us to take a much closer look. By inviting folks to look more closely, to see what he saw, William Bentley introduced the world to what he called “miracles of beauty.” Snow crystals were a kind of portal for him; they showed him the astounding beauty of Earth.

Dreams can likewise be a portal. It’s no use, however, trying to “preserve” dreams, if preservation means pressing dream images onto slides for viewing and photographing. And anyway, this would merely preserve a “record” of the dream. But if this record, like William Bentley’s photographs, invites us to take a closer look, if we are introduced to, and allowed to mingle with, the miracles of beauty in the dreamtime, and we set to work in a spirit of discovery, we may indeed find that this helps to keep the dream from melting altogether.

If, as “Snowflake” Bentley suggests, Nature combines her “greatest skill and artistry in the production of snowflakes” isn’t this also true of dreams? Of dreamers? In this season of miracles, whether one celebrates the miracle of light or the miracle of divine birth, or the miracles of unity and culture, is it not also worth celebrating that each and every one of us is a lit-from-within, unique and dreaming miracle of beauty, a masterpiece of design in Earth’s dream of us?

Here’s to all of us. Happy Holidays!

0 Comments